Three Days in Mt. Athos ⛰️

Athos is a skinny finger of land that protrudes 20 kilometers into the Ionian Sea. A spine of mountains runs the length of the peninsula and terminates in the holy mountain itself, Mt Athos. The rugged, densely forested landscape is surrounded by the choppy waters of the Ionian Sea. Clinging to the sides of cliffs and nestled in hidden valleys are many important Christian religious sites. A tangled network of footpaths connect monasteries, shrines, and orchards of fruit-bearing trees where monks grow olives, cherries, apricots, and other foods required for a simple monastic life. These footpaths, often poorly mapped, are traversed by pilgrims, monks, and wild animals. Things have changed little since the time of the Byzantine Empire.

Although a part of Greece, Athos is an autonomous region. This loophole allows the ruling religious authorities to bar entry to women, as they might distract the monks from the worship of God. Even female animals, the legend goes, are refused entry. So are most other kinds of visitors - each day only 100 Orthodox visitors are permitted to enter the peninsula along with 10 people from other faiths, and non-believers like myself are not welcome. Additionally, booking a stay isn’t a simple task: few of the monasteries have an online presence, and cloistered monks are not known for being up-to-date about technology.

In July of 2022 I went on a pilgrimage to Mt Athos, the Holy Mountain. Although I came and left an atheist, there was truly something deep and eternal about this land outside of time. It’s no exaggeration to call Athos a holy mountain. In this article I’ll describe my experience there and general tips for exploring and understanding this unique and ancient place.

Saint George the Zograf Monastery

Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name

thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven

Give us this day our daily bread

and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us

and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil

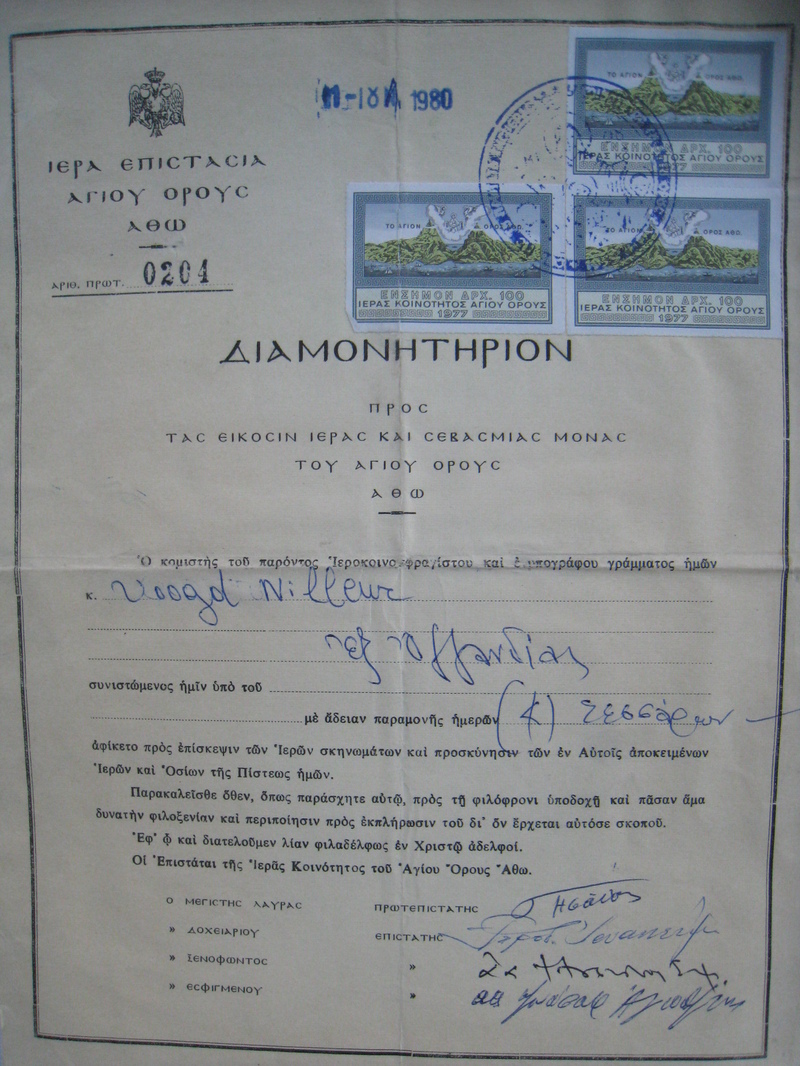

The process for entering Athos is best described as Byzantine. The religious authorities of the Orthodox Church are not sticklers for bureaucratic efficiency, and the information that does exist online is mostly oriented towards Greek- and Russian-speaking visitors. I discovered that monasteries must be contacted individually and reservations made for three consecutive nights. After reservations are confirmed, the Pilgrims Office in Ouranoupoli must be informed of your plans. A few Google-translated exchanges later you’ll be given a distressingly laconic confirmation that your visitors permit (diamonitirion) can be picked up on the day of your arrival.

Ouranopoli is the outside world’s gateway to the closed monastic world of Athos. To our pleasant surprise, we found that entry procedures were relaxed and informal. Before arriving in Greece, I’d taken some time to memorize the Lord’s Prayer and learn to cross myself in the hope of passing myself off as a Christian. Fortunately, our religiosity was never questioned - the staff at the Pilgrims Office simply asked for a verbal affirmation of our religion and collected the €20 fee. The man at the pilgram’s office then pointed us towards the ferry (the our in this sentence refers to myself and Eason, a close friend who I have traveled to Mecca, Lalish, and other adventurous places with).

All pilgrims follow the precedent set by the Virgin Mary, who, according to Orthodox tradition, first arrived in Athos when her ship was blown off course while on the way to visit Lazarus in Cyprus. Disembarking on Athos, she was amazed by the natural beauty of her surroundings. She blessed the place and from then on all other women were forbidden from entering.

Our ferry embarked under less dramatic circumstances. The sea was gentle and blue. A few elderly Greek passengers basked in the soft morning sun. The bearded monk piloting the ship looked tired but content. The long green backbone of Athos rose like a gigantic jagged wall beside us us. We could see the occassional turret or rooftop poking out of the green and splotches that might have been cultivated fields. After a half hour the ferry turned towards the shore.

The first stop on our itinerary was Saint George the Zograf Monastery. As soon as we’d thrown our bags down onto the coral white pier the ferry pulled away. The monk and elderly pilgrims waved goodbye. The port was empty. A hollowed-out watchtower loomed over us. Across from it was a barracks-like building, in front of which was the vine-covered skeleton of a truck. A rusty metal barrel was surrounded by a halo of grass. Insects buzzed loudly. The ferry vanished into the blue-on-blue horizon. Our destination was somewhere in a valley behind the port, an uncertain distance ahead. A Wikipedia article had promised “well-signed” trails in Athos. Eason discovered a fallen over sign with Ζωγράφου (Zograf) written on it. I tried to reconstruct which direction it had once pointed. This was our first inkling that things would be trickier than promised.

Although still only 9:00am, the day was hot. Fortunately, a canopy of oak and pine trees stretched over the path ahead. Already sweating, we picked up our bags and set off on the dirt path. We made a couple of wrong turns, but eventually found a cobblestone path that led uphill.

When the trees opened up we were suddenly at the foot of Zografou monastery. Its stone walls rose into the sky like a castle - a dozen stories tall. Turrets, walls, and even a strong wooden gateway in front, it was more than capable of withstanding a seige. Beyond the sturdy wooden gates was a large courtyard. Clinging to the walls on every side like barnacles were smaller wooden rooms. In the center of the courtyard was a larger structure that looked like a church. Inside were rows of black cloaks hanging from the walls, but their owners were nowhere to be seen.

We’d later discover that every monastery in Athos has a structure similar to this: a central church, a dining hall directly opposite, and monk’s quarters carved out of the walls.

We threw our bags down and rested in the shade. I peeled off my shoes and massaged my sore feet. A monk crossed the courtyard, dressed in long black robes, paying us no attention. A little while later another passed by in similar fashion, his eyes deliberately avoiding us. We began to wonder if visitors from the 21st century were invisible here, incongruous as we were. Feeling like we might be in the wrong place, we grabbed our bags and left the courtyard. Outside we found a wooden building that resembled a stable. From inside emerged a monk, covered in sawdust. He greeted us warmly and brought us to another, newer building where we met the leaders of the monastery.

The head priest, an energetic older monk, insisted that we have a drink with him. He had bright blue eyes and a scraggly gray beard and studied us like we were alien visitors, which perhaps we were. Our conversation was a confusing combination of Greek, English, and hand gestures. He wanted to know all about the United States, our journey from Europe, and our impressions of their simple monastic life. After drowning a few glasses of moonshine, we were asked to produce our diamonitirions and were shown to our room.

Sleeping quarters in Athos are all similar - an undecorated room with two to four beds, a table, towels, blankets, and an icon or two to interrupt the otherwise barren walls. Each group of pilgrims gets their own room, and things always felt very private. After all, this is a place for focusing on God, not making new friends.

There was a pleasant rain shower. I’d decided to forgo technology during my pilgrimage, so I took out a paper copy of Moby Dick and started reading. After the rain stopped, I found the leader monk and was made to understand that dinner would be served shortly.

Dinners in Athos follow a similar script. The monks enter the central church to pray. When the prayers end, they rush to the dining hall and sit in silence. Plates of food are placed before them and a passage is read from the bible. The food is simple: olives, grapes, bread, clear soup - all things the monks have made or harvested themselves. There’s no menu. You eat whatever is placed in front of you. Dinner is eaten in silence. A monk will walk around with a pitcher of wine. If you want some, you simply lift your glass. When the bible passage ends, the book is slammed shut loudly. The forks clang down. Everyone stands up, chewing their final mouthful, and leave as quickly as they entered. Mt Athos is a place where attention is directed towards God, not earthly pleasures like food.

The monks performed another prayer after dinner. As pilgrims, we were excused from this ritual, and returned to our sleeping quarters. Exhausted from our early morning and difficult trip overland from Bulgaria, we passed out before sunset.

Ivrion

The Abrahamic religions - Christianity, Islam, and Judaism - have a history of daily prayer. Although this tradition died out among Christian laypeople over the last few centuries, it’s still practiced by monks. While the five daily prayers of Islam might seem excessive, Christianity historically had seven. The morning prayers, called Matins, are performed before sunrise. When we woke up, the distant whisper of these prayers was echoing from within the castle walls.

O Lord, save your people, and bless Your inheritance. Grant victories to the Orthodox Christians over their adversaries. And by virtue of your cross, preserve your habitation. O holy Apostles, intercede with our merciful God To grant our souls forgiveness of our sins!

Nobody was to be seen when we quietly crept out of the monastery. The sun was rising, as was the humidity, promising a hot and sticky day. Ivy and blackberry creepers tugged at our clothing as we navigated the narrow trail. Eventually the path became impossibly tight and disappeared entirely. We retraced our steps and took a fork in the road we’d come across previously. Eason consulted Google maps, but it soon became apparent that the hand-drawn map I’d created before setting out was going to be more useful. Our first goal was the town of Karyes to purchase food and supplies followed by Ivrion where we’d be spending the night.

Eventualy we found a reliable path. It took us through dense forest. There were occasional clearings where monks had scratched out small vegetable patches. We climbed a tall hill and saw a patchwork environment of olive orchards in front of us. A monastery was silhouetted against the white shore of the Ionian Sea.

We hitched a ride to Vatopedion where we were given directions to Karyes. After an hour of walking, a truck driver picked us up. It was one of the only two vehicles we saw the entire day. The driver was a beekeeper and told us that he was now in the business of moving supplies across the peninsula and serving the monks. The beekeeper left us with some garbage bags which we threw over our backpacks to protect them from the occassional rain showers.

Karyes has one main street and a bus stop. Some pilgrims opt to take busses between the monasteries, but we felt that this went against the spirit of Byzantium. The main business of the town seems to be the sale of religious materials, principly icons, and there are several shops with images of Jesus, John, and Mary crowded in the windows. In what can only be described as a “holy convenience store” we bought cherries, apricots, apples, and nuts which we immediately consumed - unaware of the dining rules in Athos, we hadn’t finished dinner by the time the bible had slammed shut the night before.

The terrain below Karyes was rugged. Tall pine trees were crowded into the deeply folded land. The footpath crossed small streams and followed drainage ditches. Next to a small shrine was a spring of clear, cold water. We drank from a tin cup left nearby. Sometimes there would be a loud rustling in the bushes near the path. Wolves and wild boars - the latter especially dangerous to humans - live in the ancient and pristine forests. We feared crossing paths with a territorial animal, especially because we were the only people on the paths (we never crossed paths with another human animal).

The path led to a sharp valley. A tall stone bridge crossed the expanse. It was beautiful, ancient, and I had the sudden feeling that I was living in some kind of medieval videogame, the kind I played as a kid where you’d have to fight off thieves or find a dungeon to explore. We sat on the bridge and ate the remainder of the food we’d brought. A little ways past the bridge the path descended into a broad valley. Ivrion monastery was nestled between olive orchards. Its towers cast long shadows across the dusty landscape.

Ivrion would be the largest monastery we’d visit - there was even a dedicated “reception” area, though nobody was present to check our papers. While we waited for a monk appear, we snuck into the kitchen to steal Turkish delights, tea, and water. Later that night, after bathing and eating, I’d also steal a few postcards from the library, though I think these were intended to be taken.

Ivrion’s dining hall was enormous. Long tables spanned the length of the cavernous building. The ceiling was undecorated, like the Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo. I ate quickly, sucking up as much soup and wine as I could. Pliny the Elder wrote that the inhabitants of Athos lived extremely long lives because their diet consisted of poisonous snakes. However, we saw no meat (or animal products of any kind) on the dinner table. Perhaps a simple vegan diet is actually the cause of long life?

Afterwards, slightly buzzed from the alcohol, I washed my sweaty clothes in a sink in the communal bathroom. Another pilgrim saw me doing my chores and didn’t say anything. Public washing seems to be an accepted in a monastic community where few people own excess property. I fell asleep reading my wrinkled copy of Moby Dick.

Agiou Pavlou

The next morning we woke up late. The dusty ground outside the monastery was golden in the sunlight. We considered taking a bus to Dionysiou, the final monastery of our pilgrimage. When we realized the bus was never coming we set off on foot. My hand drawn-map was disintegrating, and we got very lost. The path took an unexpected turn, so we decided to leave the path and follow a ridge to an adjacent valley. Eason ran out of energy and we threw down our backpacks and let the sweat evaporate from our clothes.

I scouted the forest and found a small hut and a with a water faucet outside. There was a cup nearby so I took a drink and returned to Eason to tell him about what I found. When Eason approached the house, a monk came out and silently offered him a bag of food. When Eason returned, we divided the chocolate and oranges between each other and ate them quickly.

Still lost, we eventually found ourselves on a ridge overlooking a wide valley. On the other side of the valley was Mt Athos itself. Grey and white, little patches of forest and distant thundering waterfalls, it towered over the peninsula, dwarfing the smaller mountains that surrounded it. Our original plan was to summit Athos before arriving at the monastery late at night, but seeing how tall mountain was we quickly abandoned this plan. Dinocrates, one of Alexander the Great’s architects, proposed carving the mountain into the Macedonian Emperor’s likeness - however, the hugeness of the mountain in front of us made that idea seem comical. Athos took up half the sky.

Below us, far in the distance, was Dionysiou. We descended but realized we’d taken the wrong path. We tried backtracking, but couldn’t find a road that led down into the valley. A little further on there was a fork in the road that seemed to lead to another monastery. The sun was getting lower on the horizon and we decided to cut our losses and aim for this one instead. We took another wrong turn, backtracked, and eventually found a steep path leading down to the monastery. Eventually this path widened into a proper road, and a passing SUV stopped to offer us a ride.

Surprisingly, the monk driving the car spoke English. We explained our predicament and he assured us that there would be an extra room in the monastery. We were led beneath the crenellated walls where the head monk greeted us and informed us, also in English, that we had arrived at Agiou Pavlou. It was thanks to the grace of god, he explained, we were just on time to join the afternoon prayers that precede dinner.

The prayer session was relentless. There was chanting in Greek and Russian. We copied others as they bowed and clasped their hands and chanted their praises to the holy trinity. After a half hour my feet were aching. I was amazed by the zeal of the monks, who pray like this for hours every day. As the prayers concluded, a long line formed in front of the altar. The visitors were given the rare opportunity to worship a variety of holy icons. After kissing an icon of Jesus (who had also been made out with by dozens of other hopefully vaccinated visitors) we were shuffled into the dining hall for another silent dinner.

Later that night we were invited to the office of the head monk. He was energetic and intelligent, asking us questions about the USA and cracking jokes about American and European politics. He wondered how we felt about Athos and Greece more generally, and was excited when we gave a favorable assessment. As a Greek, he told us he was obliged to offer us tea and snacks, which we consumed quickly. He then took us to a balcony that overlooked terraced fields that stretched down to the sea. The view was beautiful, and the monk was clearly proud of how impressed we were.

The head monk informed us that Orthodox Christians are especially interested in the lives of the saints. Knowing that we were both from the West Coast, he told us the story of Seraphim Rose, a monk from California who lived an austere life of prayer in the coastal redwood forests. Orthodox Christian monks set themselves apart from the secular world to devote themselves to the worship of God. An important part of this is the practice of hesychasm, where monks will continuously repeat the Jesus prayer in order to create a feeling of inner stillness and contemplation.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Later that evening we were woken up by rhythmic chanting, maybe the Jesus prayer. When the chanting stopped a rainstorm started. We slammed the windows shut and slept until daybreak.

Thessaloniki (the 21st Century)

The head monk had told us that a ferry back to Ouranopoli would depart from the port below Pavlou “just after sunrise.” Not wanting to miss our only chance of returning to civilization, we headed to the port immediately after waking up. A little while later we were joined by a small group of elderly pilgrims.

As we waited, we explored small caves that had been carved out by millenia of erosion. Homer desrcibes the stormy waters of the Ionian Sea as being “wine dark,” but today the calm water looked like glass. On the horizon were the tops of distant islands. I imagined hopping in a trireme and exploring these distant shores. Despite its importance as a Christian monastic enclave, Athos has pagan origins. Its name comes from a giant that Poseidon defeated and buried under the holy mountain. For centuries before the rise of Christianity pagan Greeks fought, traded, explored, and sacrificed to their pantheon of gods on these holy shores. The Christian presence here seems to echo an older and deeper sacredness connected to the peninsula’s water, earth, and natural life itself.

Back in Ouranoupoli we found the car and set out for Thessaloniki. Athos narrows to a thin isthmus before it reconnects with the Greek mainland. Here, in the 5th century, the Persian king Xerxes dug a canal to assist his invasion of southern Greece. Prior to the canal’s construction, much of the Persian navy was destroyed in a storm in the dangerous wine dark waters that surround the peninsula, necessitating this shortcut. Today the canal is completely silted up. Apart from a sign, bilingual in English and Greek, nothing indicates that this was once one of the ancient world’s greatest engineering feats: just a few scraggly bushes, cracked clay soil, and a rusty chain-link fence.